Nat Geo Special Expedition to Osa Peninsula!

Saturday 28 April, 2018 - Author: Undersea Hunter

©Manu San Felix © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

We’re just back from an exciting 20-day expedition with the National Geographic Pristine Seas team, led by Enric Sala and Paul Rose!

The ultimate goal of the Pristine Seas project is to “find, survey, and help protect the last wild places in the ocean.”

In addition to photographing, filming, and thoroughly documenting the area the team also corroborated with local politicians with the aim of creating a ~18,000 km2 off the Osa Peninsula.

The trip was a huge success, a collaboration between Pristine Seas, Osa Conservation, and the Universidad de Costa Rica — and of course Undersea Hunter!

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

Part 1: The Expedition in a Nutshell

We started the first half of the expedition at Caño Island, where we discovered a surprising richness and abundance of fish life. The team took some stunning images of colorful corals, giant schools of fish, and large animals like mantas.

The presence of such big creatures demonstrates the area’s importance as a habitat for pelagic life like humpback whales (in fact, this is perhaps the only place in the world where there is an overlap in migratory routes between northern and southern hemisphere humpback populations). Other large species include various sea turtles, whale sharks, Bryde’s whales, false killer whales, rough-toothed dolphins, bottlenose dolphins, spotted dolphins and spinner dolphins. One of the most unforgettable trip moments was the spinner dolphin superpod we encountered two days in a row about 20km/12.5mi offshore. DeepSee chief of operations Shmulik Blum recalled: “Most striking about an encounter with a superpod is the overwhelming sound in the water…it’s the most amazing thing.”

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

After abo ut a week at Caño Island, we traveled southward to Matapalo and then back up to Sierpe.

These areas are constantly battered by high energy waves and debris, making it difficult to study. We sampled several places along the coastline, and then worked our way back to Caño Island where we prepared for our open-ocean tour.

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

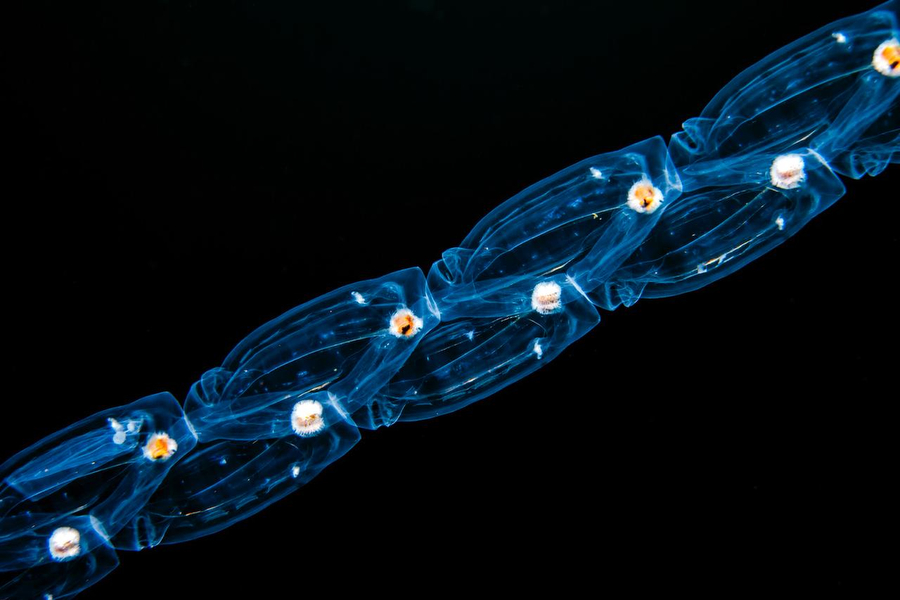

Out in the proverbial “middle of nowhere,” we performed blue water dives where our scuba divers randomly jumped into the sea far offshore.

There we found all kinds of surprising, alien-looking plantonic gelatinous creatures.

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

The Argo and DeepSee continued to drift for about a week, stopping at various reference points and places of interest. Nat Geo effectively observed local methane seeps, which are basically formed when gas accumulates under the crust of the Earth and slowly starts to be released through the bottom of the ocean

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

Scientists were fascinated to study a bacteria that lives in the gas, which can actually process the gas to generate energy through a sort of chemical synthesis. Because these seeps might be of commercial interest in the near future, it’s wise to get a baseline study of them before any kind of industrial impact presents itself. This will allow for smarter government management of this resource.

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

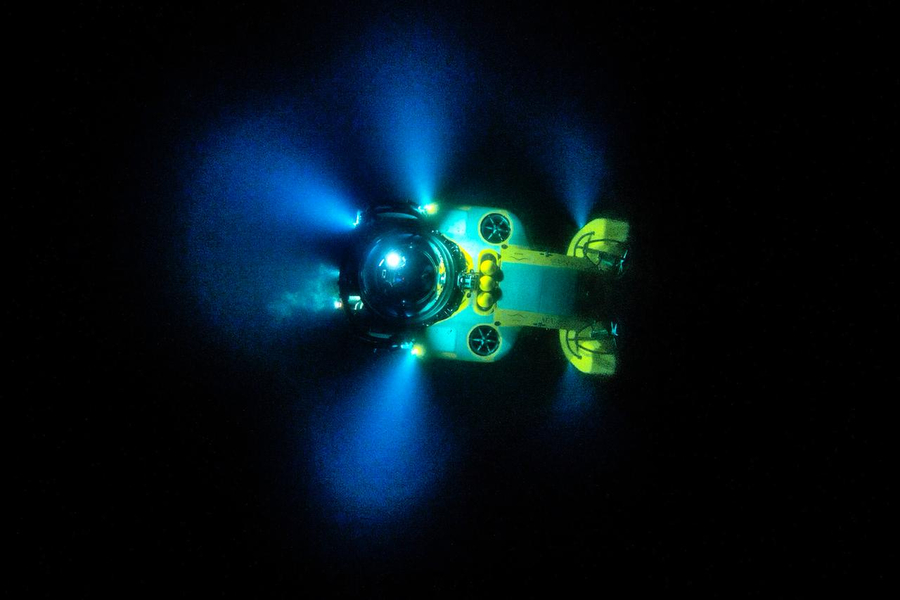

The DeepSee sub was truly an invaluable resource for these deep sea studies. We collected corals and compact mud cores ½ meter deep into the bottom. By looking at the sliced mud, researchers can learn all about the microbes currently living in the substrate – and they can also see which may have died in there millions of years ago.

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

Over the course of the expedition Paul Rose held two virtual classrooms in the Argo’s media room, where kids were able to connect over the internet and ask questions in real time. At one point Costa Rica’s Minister of Environment made an appearance to show his support, along with 12 government local head of communities and municipalities. Afterward, many of these diplomats attended an event in Drake Bay where Carlos Hiller painted a huge mural.

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

Part II: Behind the Scenes

This was Pristine Seas’ 7th expedition with Undersea Hunter in the past 10 years – starting with a Cocos Island trip in 2009, followed by Desventuradas Chile; next the Revillagigedos; then Clipperton; the Galapagos Islands; Malpelo Island and now the Osa.

Pristine Seas presents a unique challenge demanding utmost efficiency and know-how. Many elements are in motion simultaneously; scientists study from the shallow to the deep, all the while with a media team constantly filming in the background (both topside and underwater).

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

The Argo is the obvious solution to such a complex voyage, and we were fully prepared for the challenge – equipped with four skiffs (including a special skiff dedicated to the pelagic cameras), a submarine and an experienced crew that orchestrated everything seamlessly. In fact, we have developed a custom conversion setup just for the Pristine Seas team that allows us to anticipate their needs and provide a hyper productive experience.

In 20 days we completed 360 scuba dives, 27 submarine dives, 169 pelagic camera deployments, 27 deep-sea camera drops. It doesn’t get more productive than that!

To establish an estimation of the biomass of species in the area, Nat Geo Pristine Seas executed 5 main methods of research:

©Shmulik Blum © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

1.) SCUBA

A scuba diving science team that goes down to 40m

2.)BRUVs (Baited remote underwater video stations)

These are weighted camera setups dropped into water that are attached to a bait bag. They are stereoscopic, meaning two photos are taken of the same object or animal that comes close. Special software puts the footage together to estimate size.

3.) Pelagic cameras

This system is similar to the BRUVs, but instead of having a weight and sitting at the bottom they float on a long line on the surface looking at pelagic creatures like dolphins, whales, fish etc.

4.) Submarine

The DeepSee submersible studies the mesophotic area to the twilight zone, between 50m-450m. We took people down each day to collect samples.

5.) Drop cams

These remote cameras look like glass spheres that are dropped down into extremely deep water — they can easily reach the bottom of the ocean. They are weighted, baited and sunk to bottom where they remain stationary. Every so often, the lights will turn on and the programmed camera will record for about a minute. Then it will shut off. This sequence repeats itself for 2-3 hours before the camera is released from its weight and floats to surface. From there, we jump on the dedicated skiff and collect it.

All in all, this was another incredible journey! According to Nat Geo, this important work will “provide a much more thorough understanding of how the entire ecosystem functions, therefore helping to inform better management of this unique area.” A documentary film is in the making, as well as a scientific report summarizing the expedition’s findings concerning the deep sea/pelagic ecosystem as well as the micro fossil and paleo ecology of marine sediments.

©Avi Klapfer | Drop cams used by Nat Geo Pristine Seas expedition

© photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Avi Klapfer | Preparing to fly a drone from our state of the art drone launch pad © photo by Undersea Hunter Group

©Shmulik Blum | Pelagic cams used by Nat Geo Pristine Seas expedition © photo by Undersea Hunter Group